A company that began with a partnership between two NC State University Professors is tackling organic solar cell research head on, presenting their work at a Research Triangle Park tech summit late last month.

Brendan O’Connor, a Professor from NC State’s Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, partnered with Distinguished Physics Professor Harald Ade in 2021 to created PolyPV in response to a call to action from the Office of Naval Research to develop commercial organic solar cells. The company’s lead engineer, Dustin Abele, presented the company’s progress last month at Venture Connect 2023, a technology summit where nearly 200 companies met to pitch their ideas and establish strong partnerships and innovative solutions.

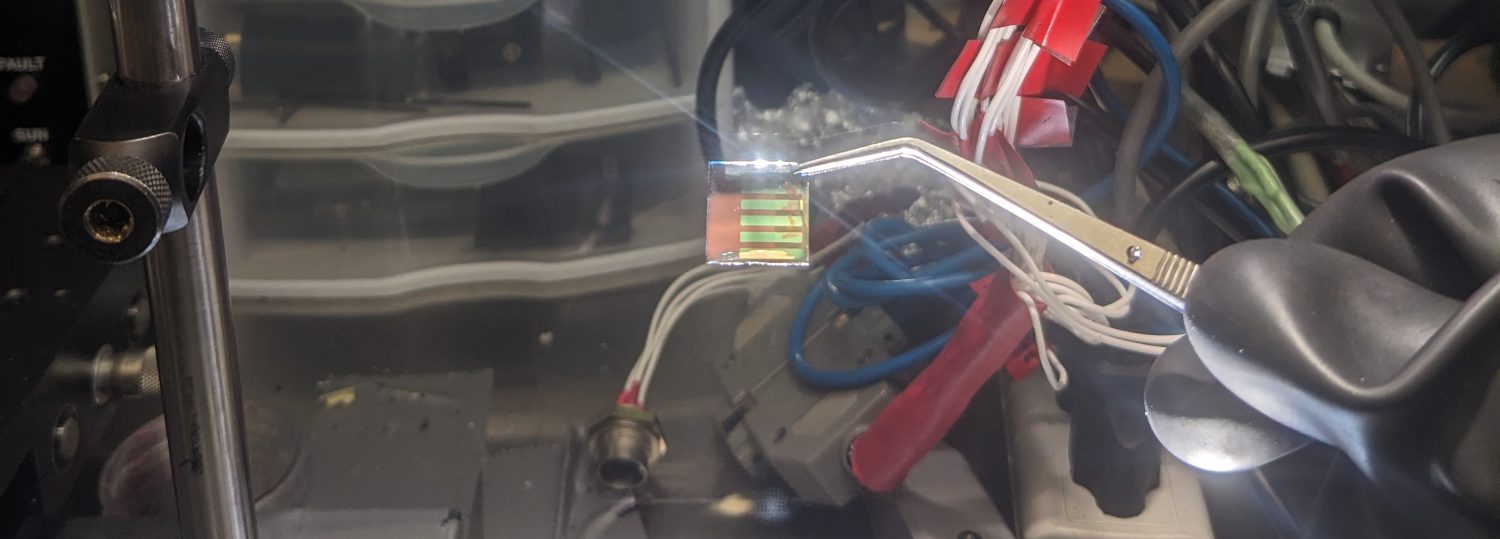

“Organic solar cells are just solar cells made out of organic semiconductors. For example, the most commercially available organic electronic device has been OLEDs, like OLED TVs and displays,” O’Connor said. “The concept of organic solar cells is quite similar to that, except with OLED you’re applying electricity and getting light out, whereas with solar cells you’re taking light in to produce electricity.”

O’Connor and the rest of the team at PolyPV have set out to give polymer solar cells to the mechanical properties and ruggedness of plastic, which has a variety of benefits to the efficiency and integrity of the product.

“We’re essentially trying to make plastic solar cells,” O’Connor said.

The benefits of PolyPV’s organic cells are abundant, and aid in improving solar cell technology for both military and commercial applications.

According to O’Connor, the military is interested in remote power and the polymer solar cells are far more resilient, flexible and lightweight when compared with traditional cells, allowing it to be applied to things like backpacks or tents and transported to different locations.

The ruggedness and lightweight nature of these cells also allows for a number of commercial applications, such as in the context of outdoor recreation and camping, O’Connor said.

“There are still challenges though,” O’Connor said. “We have to make them mechanically robust, we have to make sure they can live a long time; so that’s what our focus is in these areas.”

While O’Connor largely focuses on the strength and and flexibility of the PolyPV cells, he and Ade are both seeking to address the issue of the ensure that they can maintain the benefits of these cells, while also working within the ultra-thin nature of an organic solar cell, which is only around 200 nanometers thick.

O’Connor also noted that the founding of PolyPV and the work that they do falls at a very exciting time for the solar cell industry, and they are specifically one of very few U.S.-based companies to pursue such research.

“The field of organic solar cells has been really interesting in recent years,” O’Connor said. “There have been some efficiency and stability issues – people were making them commercially at only around 3% efficiency – but right now organic solar cells are knocking at the door of 20% efficiency. So, I think this technology is ready to be commercialized.”

PolyPV has successfully secured a Phase II STTR (Small Business Technology Transfer) grant to further the development of their next-generation organic solar cells. They are currently developing a robust IP portfolio, strategic partnerships and looking for investments.